An In-Between Time for Miles Davis

The Miles Davis Quintet live at the Tivoli Koncertsal in Copenhagen, November 4, 1969

Miles Davis often gets compared to Pablo Picasso because, like the Spanish master, he went through several distinct, iconoclastic artistic periods that profoundly altered the course of his genre. Neither artist ever looked back either, and that's why Davis' concert on November 4, 1969, at the Tivoli Koncertsal in Copenhagen might come as a surprise. Three months earlier, the five men onstage had been among the musicians who recorded the landmark Bitches Brew. It was Davis' new direction, absorbing contemporaries like Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix, and prominently featuring novel instruments such as the bass clarinet and the electric guitar, as well as straight-ahead rock-influenced beats that punctuated a palpable sense of space. You'll hear none of that during this concert. The band includes Wayne Shorter, a holdover from Davis' previous quintet, on sax; electric keyboardist Chick Corea; stand-up bassist Dave Holland; and drummer Jack DeJohnette. Each of them soon to be giants of jazz fusion, they're called Davis' "lost quintet" because they never made any studio recordings as a fivesome. That's why, as flawed as this performance may be, it's a valuable and vivid document. It's just so perplexing that the show sounds nothing like Bitches Brew.

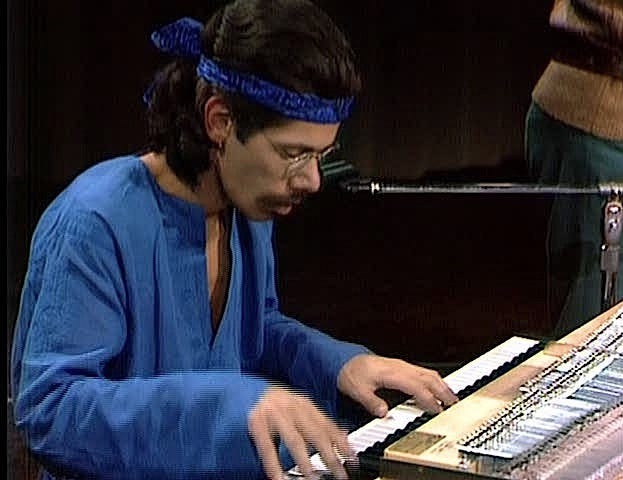

At the Tivoli, the band is so raring to go that they begin playing before the theatre's phantasmagorical curtain even opens; Corea plays a figure on the Rhodes keyboard and, right on cue from DeJohnette's deft drum flourish, the curtains swing open to reveal the band and Davis himself, who is resplendent in a psychedelic outfit: a multicolored vest, deep blue scarf and a hot pink shirt with a collar wide enough to fly a 747. They kick into "Directions," their standard opener at the time.

Davis and Shorter announce the theme once through, then it's off to the races. Davis' studio recordings from this period through 1975 were edited by Teo Macero, who deliberately featured Davis' soloing. That doesn't happen here — instead the band goes through the batting order each time: Davis, Shorter, Corea. "Directions" sets a precedent for the rest of the night: typically, Davis leads off the tune with only the vaguest suggestion of the head melody, like someone dashing off a signature rather than fully writing out the letters, and commences soloing far more dramatically than he ever had before, less pithy and more impassioned. The rhythm section hangs relatively tight while Davis solos, but as soon as he's done, it's like when a teacher leaves the classroom and the kids run riot.So that's one difference from Bitches Brew. Another is in the groove. The contemplative and yet electrifying In A Silent Way had been released to a rapturous reception a couple of months before and yet the starkness and steady, straight-eighth-note rhythms of that album, not to mention those of Bitches Brew, just aren't here. And everyone fills every square inch of the sonic canvas, completely at odds with everything Davis had been doing for the past fifteen years, and especially Bitches Brew. Why doesn't it, for lack of a better word, rock? For one thing, there's no rock instrumentation in the band: Bitches Brew electric guitarist John McLaughlin was unavailable at the time — he was now with former Davis drummer Tony Williams' band Lifetime. There's Corea's electric Fender Rhodes piano but without the Dr. Who-like ring modulator effect he would adopt the following year. DeJohnette plays rollin' 'n' tumblin' jazz drums, and rather than an electric bass, whose sheer air-moving gut-punch lends a very different force to any band, Holland plays free, non-repeating lines on an acoustic stand-up bass. It was only after Holland left the following year, replaced by Stevie Wonder's much more groove-oriented electric bassist Michael Henderson, that the funkified sound of Davis' electric period emerged.

Instead, this is the extreme fringe of "time, no changes," Davis' approach with the previous quintet, expanded into an entire hour-plus set of continuous music located between the more standard structures and tonality of the previous line-up and the free jazz that Davis had so determinedly avoided in his search for another way forward. You don't even need to watch the DVD to understand that the band is in transition — it's right there in the set list. Older numbers like "Agitation" and the Sammy Cahn-Jule Styne standard "I Fall in Love Too Easily," both of which the justly hallowed Shorter/Herbie Hancock/Ron Carter/Tony Williams quintet played two years earlier on a European tour, share the bill with as-yet-unreleased tunes with funky titles like "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down" and "Bitches Brew." They don't play anything from In a Silent Way (although "Directions" had been recorded during those sessions). It's yet another in-between time for Davis.

The previous quintet played tight and fast — their microprocessors were faster than yours and mine — like a sporty Italian convertible. The music turned on a dime from febrile to spare and meditative, and everything, even the explosions, was impeccably articulated. It was no coincidence that that band sported tuxes and bow ties. But in the yawning gap between 1967 and 1969, things had changed dramatically. Davis' band was now less like a finely tuned Alfa Romeo and more like a Camaro with no muffler, especially with the constant roar of the bass and drums. Where bassist Ron Carter and drummer Tony Williams would often drop out and let the other players set off on interludes, Holland and DeJohnette just established a relentless rhythmic undertow and the soloists blew over it with little subtlety. Hello, 1970s! Even their clothes tell the story: instead of the matching tuxes of only two years before, the band sports bell-bottoms. For better or worse, the music embodies the times — tumultuous and self-indulgent. Individually, the musicians are mostly brilliant but the combination just isn't strong at this broken place in Davis' development. The previous quintet wrung astonishing creativity from established forms; the new quintet was on the way to destroying those forms. The mercurial Shorter alternates between non-committal doodling and unabashed imitations of Coltrane's "sheets of sound"; it's not his night. But perhaps the prime offender is Chick Corea. While Corea's comping is interesting throughout the gig, his solos are a much different story — rather than developing anything thematically or taking the music into a compelling new direction, he simply plays neurotically fidgety little runs, dashing off the same kind of scrabbling solo on virtually every tune, the pianistic equivalent of a Cy Twombly painting. Midway through Davis' solo on "Bitches Brew" the band hits one of the evening's few solid grooves, but then everyone comes to a grinding halt during Corea's noodley, interminable solo — and rather yielding to a jazzy sense of space and dynamics, it just seems like the rest of the band collectively gives up on trying to play with him.

Things improve after the frenetic "Agitation," when Davis takes it down with a heartbreaking solo turn on "I Fall in Love Too Easily," with Corea chiming in with sparse chords. Davis' solo is almost shockingly intimate, like a late-night confession, at one point his impeccable tone breaking with emotion; it's in deep contrast to the preceding pyrotechnics. It segues into an abridged take on "Sanctuary" from Bitches Brew, featuring Davis and Shorter playing an extended theme in exquisite unison. Shimmering, weightless, and mounting to a thundering riff-storm, it's one of the highlights of the set. The Nawlins strut of the album version of "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down" surfaces briefly and highly abstracted — but then, as usual, the rhythm section completely atomizes under Shorter's solo. "Bitches Brew" hits a groove too, but it's a much different piece from the album version's several vividly etched motifs and funky pulse. Besides lacking John McLaughlin's electric guitar, there's none of that electrifying echo on Davis' trumpet, even though it was certainly possible to do that live in 1969. The tune's killer one-note bass hook is downright vestigial. It isn't until the closing number, "It's About That Time," that we get a glimpse of what this band was capable of. As ever, the groove lapses into entropy during Shorter's solo. Corea does his fidgety neurotic schtick once again, but this time, Holland and DeJohnette join in and it sounds kind of great, although maybe a bit uncomfortably like one of those "Shreds" videos. Holland follows with a spectral bowed solo, one of the most riveting moments of the entire set. When Davis comes back in, brilliantly picking up Holland's vibe with a coolly economical solo, you’re reminded of how it could have been for the whole set. DeJohnette kicks in with the only straight-ahead beat of the entire evening until Davis cuts it abruptly short with "The Theme," the little riff he'd been closing his shows with for years. To be fair, they were having an off night — other shows on the tour, like the Salle Pleyel show in Paris the night before and the show in Rotterdam several days later, are much better, mostly because Corea isn't doing his best impression of a skittish cat. It's just bad luck that this was the show that got videotaped.

And I'm not the only one who thinks Corea stunk up the gig — as they get ready to leave the stage, Davis glowers at his keyboardist, shooting him a look that could kill small mammals. Corea knows he's in the doghouse and in an awkward move that former Richard Nixon secretary Rosemary Woods would have admired, deliberately avoids his boss' devastating glare. Davis must have been really pissed: Picasso never had to put up with this kind of thing.

I've seen this video before and this being one of my favorite Davis lineups, I agree it was definitely an off night for the band. I missed Davis' glaring at Chick at the end though lol!

The At The Fillmore East double album they recorded was phenomenal though and really shows how incredible these guys were together.