Dickie Goodman, Goofball Pioneer of Postmodernism

How novelty record king Dickie Goodman kind of invented sampling

Imagine a single that sampled Drake, Taylor Swift, Ed Sheeran, and Lady Gaga — without permission — and then hit #3 on the Billboard charts, selling more than a million copies. That's right, you're imagining the mother of all lawsuits. But you're also imagining something that pretty much already happened — in 1956.

That was when 21-year-old Dickie Goodman, along with partner Bill Buchanan, recorded "The Flying Saucer," parts 1 and 2, on a reel-to-reel tape recorder, parodying Orson Welles' infamous 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast with a frenetic, freewheeling skit about an alien invasion, brazenly incorporating snippets of hits by Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins, Bill Haley and about two dozen other musical giants of the day.

REPORTER: Pardon me, madam, would you tell us what would you do if the saucers were to land?

WOMAN ON STREET #1 (Little Richard from "Tutti Frutti"): Jump back in the alley!

REPORTER: Thank you and now this gentleman there…

MAN ON STREET #1 (Fats Domino from "Poor Me"): What I'm going to do/ Is hard to tell.

REPORTER: And the gentleman with the guitar, what would you do?

MAN ON THE STREET #2: (Elvis Presley from "Heartbreak Hotel"): Take a walk down lonely street…

No one had ever done this before. It would be five years before electronic music pioneer James Tenney cut up Elvis Presley's version of "Blue Suede Shoes" on the musique concrète classic "Collage #1 (Blue Suede)." No doubt about it, Dickie Goodman saw far beyond the curve. He was basically sampling and mashing up hits of the day to concoct manic mélanges of sound years before the members of Public Enemy were even born. In the process, he pioneered the fine art of sonic copyright infringement. Some 17 record labels sued Buchanan and Goodman for poaching their music but, being the wise-ass punks they were, the duo responded with yet another of what they called a "break-in record": "Buchanan and Goodman on Trial," which bit Nat King Cole, Little Richard, Elvis, the Dragnet theme and a bunch of Martians. They got slapped with an injunction, but New York State Supreme Court Judge Henry Clay Greenberg deemed the work a parody and therefore subject to fair use laws; Buchanan and Goodman, the judge opined, "had created a new work." This was revolutionary. Buchanan and Goodman soon went their separate ways. Buchanan started a jewelry-importing business but Goodman continued to make break-in records for 30 more years. His formula was simple and unvarying: Goodman would act as on-the-spot reporter and his subjects would reply in the form of snippets of current hit songs. The '50s recordings explicitly trade on the contrast between Eisenhower-era mediocrity and the complete freakiness of the rock & rollers of the time. It's fitting, then, that Goodman debuted with a piece about Martians — to a lot of Americans, those early rockers really did seem to come from outer space. (And the jury is still out on Little Richard, bless him.) While he anticipated a key aspect of the future of popular music, Goodman also saw clearly into the present: his oeuvre works as a remarkably comprehensive index of U.S. pop culture that spans virtually the entire Cold War era. By the late '50s, Americans had become obsessed with flying saucers, ostensibly because of the advent of the space program, although surely the escalating Cold War had led people to sublimate their anxieties about invasion and/or nuclear annihilation by obsessing on space aliens (just as the Japanese personified the A-bomb as Godzilla and other mega-monsters.) Russia’s launch of the first man-made satellite, Sputnik, in 1957 only intensified the situation. Indeed, that embodiment of the capitalist-Christian complex himself, Santa Claus, winds up in "Sputnik jail" on the Soviet-phobic "Santa and the Satellite" (1957), which went Top 40. On "Russian Bandstand" (1959), all the music is backwards, and anyone who doesn't like it gets mowed down by a machine gun. Amid the escapist mood of the early and mid '60s, Goodman took on cultural phenomena like Beatlemania ("Frankenstein Meets the Beatles"), the massive hit TV western Bonanza ("Schmonanza"), dance crazes ("The Cha-Cha Lesson") and Lawrence Welk ("Stagger Lawrence," which mashes up the famously bland easy-listening king with Lloyd Price’s cheerfully violent 1959 hit “Stagger Lee”). But later in that tumultuous decade, domestic politics dominated the nation's collective consciousness and Goodman released topical tracks like "On Campus," about the unrest at the nation’s universities, and "Washington Uptight," in which Goodman quizzes 1968's various presidential candidates. (California governor Ronald Reagan consistently answers with the chorus line from the middle-of-the-road classic "Windy.") On the occasion of the first lunar landing in 1969, Goodman "interviewed" the astronauts in "Luna Trip":

REPORTER: What was the first thing you saw when you set foot on the moon?

NEIL ARMSTRONG (Desmond Dekker): Ohhhh, the Israelites...

Goodman's over-caffeinated Long Island squawk was hardly Cronkitesque, but that was just part of the joke: back then, it was positively absurd to think of politicians and journalists in a pop cultural context; journalism and show-biz existed in separate spheres. Bu today, our president is a former "reality" TV show host, the New York Times covers celebrity feuds and morning news anchors make the gossip columns. No wonder Goodman's humor doesn't work as well now.

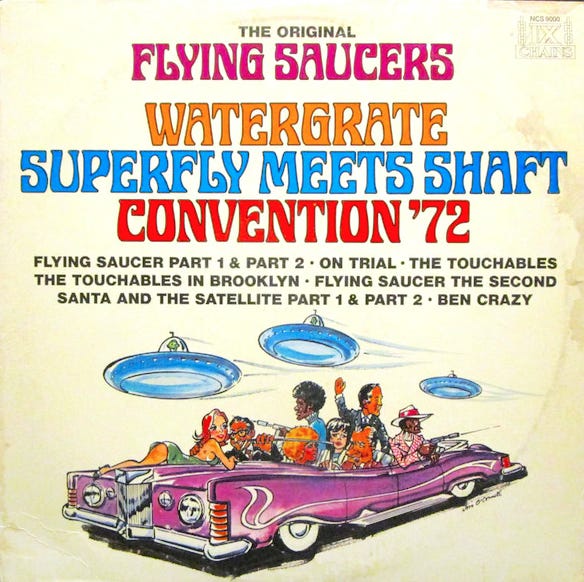

The media landscape wasn't so fragmented then — we all heard the same Top 40 hits, we all watched the same sitcoms and movies, and almost twice as many Americans watched the nightly news in the '70s as they do now; everyone got the reference points. Goodman documented the nation's souring mood during the Nixon and Ford eras with tracks like "Watergrate" [sic], "The Constitution," "Mr. President," "Inflation in the Nation," and "Energy Crisis ‘74" (which made it into the Top 40), rarely taking sides, merely weathervaning with popular sentiment. At the same time, he dipped into the blaxploitation movie trend with a couple of his best productions: 1973’s "Superfly Meets Shaft," a top 40 hit credited to the Original Flying Saucers, bit Curtis Mayfield, Joe Tex, the Spinners, the O’Jays, Isaac Hayes and others, and Goodman's production for John & Ernest, "Soul President Number One" sampled James Brown, Billy Preston, the Dramatics, the Temptations et al. Goodman kept recording and releasing records for years, releasing dozens of singles, and his work always popped up on Top 40 radio or Dr. Demento’s widely syndicated novelty music show. But nothing made a significant dent in the charts until Goodman jumped the shark. It's hard to convey the obsession America had with Jaws, both as a magnificently scary film and as an unparalleled blockbuster — in the summer of '75, it was all anyone could talk about. Naturally, Goodman took note and, with James Taylor, the Eagles, the Captain and Tennille, the Bee Gees, and other Bicentennial-era superstars on board, "Mr. Jaws," reached #4 on the pop charts and went gold, his biggest success since "The Flying Saucer" 19 years earlier. The following year, Goodman tried to ride the coattails of another movie monster — the would-be blockbuster remake of King Kong — but even with the unwitting participation of Rod Stewart, the Eagles, Stevie Wonder, and Barry Manilow, his "Kong" bombed even worse than the movie did. Dickie Goodman never charted again. I was working at MTV News in late 1989 when a call came in from Goodman's son Jon: broke and broken-hearted, Dickie had died by his own hand, age 55. The inscription on his grave reads, “Warm his heart, Mr. Sun, because he just can't stand the pain and please bring him back if you can again.” Goodman lived just long enough to hear sophisticated progeny like Plunderphonics and Negativland, but missed out on using ProTools, not to mention documenting the fall of the Berlin Wall (just a few days after his death), Seinfeld, the O.J. trial, The Simpsons, the internet, Bill Clinton's infidelities, Titanic, and the Iraq War fiasco; he also never had the chance to sample hit songs that were themselves composed of samples. Dickie Goodman may not have been a comic genius, but he was a sonic visionary and, for decades, a fixture of the pop cultural landscape. As another casualty of the American dream once said, "Attention must be paid."

I used to love these songs when I was growing up! I thought they were clever and funny. I even used to create my own versions on a cassette recorder for my own amusement.