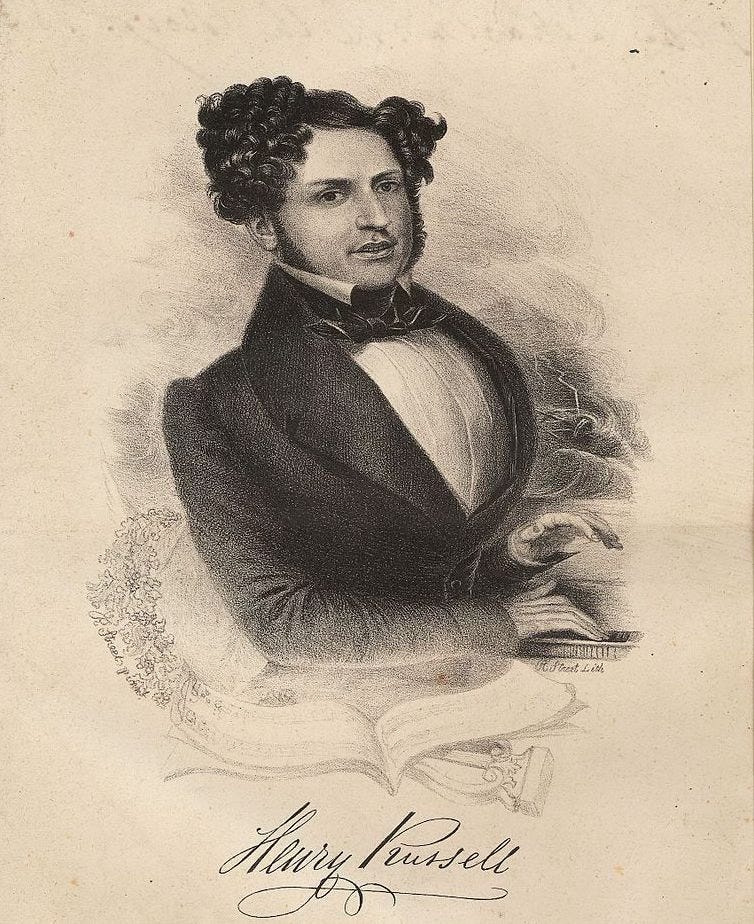

It's said that every person will someday be forgotten — even very famous people. So, while researching the Song of the Earth/"Old Folks at Home" post, I started wondering about other songwriters, besides Stephen Foster, who were big stars in the 19th century but are now very obscure. Turns out there were a few — and one of them was Henry Russell. I'd never even heard of him before but he wrote some of the most popular songs of his time. A classically trained singing Englishman, Russell came to America in 1833, when he was about 20 years old, seeking musical fame and fortune. Early in his eight-year tour of North America — just imagine what that must have been like! — he hit upon a winning commercial formula:

"One afternoon when I was playing [the organ] at the Presbyterian church, Rochester [New York], I made a discovery. It was that sacred music played quickly makes the best kind of secular music.”

Russell first used that approach to write "Get Out o' de Way Old Dan Tucker" — or at least he claimed he wrote it, since the authorship of the song is disputed — basing it on the stately 16th-century Christian hymn "Old Hundredth." It was a hit on the odious minstrel circuit. About 170 years later, in 2006, Bruce Springsteen covered "Dan Tucker" on We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, but not before it was covered in the 20th century by leading bluegrass, folk and country artists such as Uncle Dave Macon, Oscar Brand, Cisco Houston, Doc Watson and Burl Ives, and heard on TV shows like The Andy Griffith Show and Little House on the Prairie. Russell wrote that he used the hopped-up sacred music trick for several more songs: "Lucy Long," "Ober de Mountain" and "Buffalo Gals" (which Springsteen also covered on the Seeger Sessions album), another song whose authorship is disputed. The funny thing about the "sacred music played quickly" ploy is that — more than 130 years later — Ray Charles and Sam Cooke basically did the same thing with Black gospel music and also became huge stars. There must be something to that gimmick. Russell knew what it took to write a hit: according to the Dictionary of National Biography (1901) the themes of his songs "were of so essentially domestic and popular a nature that they at once caught the fancy of the public." (Another perennially winning pop formula.) And, thanks to his paying close attention to the famously passionate orations of Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, Russell's performances had "a dramatic intensity which thrilled his hearers." He was a rock star! Henry Russell eventually composed about eight hundred(!) songs, including "Cheer, Boys, Cheer," which Stories of Famous Songs, Vol. 1 (1906) described as "once universally popular." But I bet there are few people alive today who have even heard of the song. There were other hits too — "A Life on the Ocean Wave," "Woodman, Spare That Tree," "There's a Good Time Coming, Boys" — that won Russell "extraordinary success." "Woodman, Spare That Tree" alone sold three million copies of sheet music (and naturally, Russell saw very little money from it), decades before the Victrola, when many middle-class households boasted a piano and someone who could read music. In 1841, Russell returned to his native England and repeated his success there, touring Great Britain and writing more hits, such as "Ivy Green," with lyrics pulled from a poem in Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers. There's a whole lot more to his story: Russell was first a child star of the musical stage, studied with Italian opera composer Vincenzo Bellini, had many adventures in North America, was later an Abolitionist and became surely the first internationally famous Jewish pop song composer, many years ahead of Irving Berlin and George Gershwin. Henry Russell died, contented, comfortable and still writing songs, in 1900 at the age of 88.